- Home

- Ari L. Goldman

The Late Starters Orchestra Page 8

The Late Starters Orchestra Read online

Page 8

Judah laughed. Dominic smiled, raised his baton, and the music started. Well, it sounded like music but soon deteriorated into cacophony. Everything went awry, even the vibrato. The cellos were way ahead of the violins and no one was in tune. “Why are you racing ahead?” he asked the cellos. “Okay. Who started it? Who is the ringleader? There’s always a ringleader. Raise your hand if you are the ringleader.” No one did.

Dominic scowled. “Good. You already know the first orchestra rule. It goes like this: If you make a mistake and the conductor asks, ‘Who was that?’ say, ‘It wasn’t me!’ Blame someone else.”

I watched Judah to see if he was mortified or amused. He was laughing so hard he could hardly play.

Judah’s “repertory class” was taught by Nancy, a tall and lanky woman with big hands who seemed born to play the cello. She towered over the little children in the room even when she sat down. Her cello seemed formidable. The children, with half-size and quarter-size instruments, sat in front of her. A group of parents, some with notebooks open, ringed the room. Nancy put everyone at ease by having the children bang out tunes on their cellos and strum them like guitars. She had them play certain pieces together and then sent the parents out of the room. “That’s new for Suzuki,” one mother commented as we filed out and stood in the hall. (Suzuki seemed to have a never-ending appetite for parent involvement.)

Thirty minutes later we were invited to return and, after we took our seats, the children treated us to a “concert” of songs that they learned in our absence. It was a way of moving both the kids and us parents toward musical independence.

Later, a cellist named Rick held a “master class” that was limited to four students. It took me awhile to understand his method. He began by zeroing in on one child, asking him or her to play the newest piece of music they were working on. He’d wrinkle his brow and then pick out one aspect of their technique—the way she was holding the bow, the way he was sitting, the way her thumb grasped the neck of the cello—and have them repeat the music. He’d make the slightest correction and then ask them to play again. “Good. Much better,” he’d say.

There are so many moving parts when it comes to playing the cello. First there is the human body, starting with the ten fingers, all of which are engaged in some way with the instrument. The cellist’s feet must be planted firmly on the ground, the butt on the chair sitting at a right angle to the back, the arm grasping the bow yet flexible enough to reach across the full range of four strings. Then, there is the cello itself with the four pegs that are used for tuning and the metal end pin on which the instrument pivots when played.

Rick felt that Judah’s left shoulder was too high. “You’re tensing up. No need to do that. Just drop your shoulder down,” he said. He gave Judah a good way to remember to do this. “Before you begin, raise your shoulder to your ear and then drop it down. Raise it and drop it. Good, that’s it. Now pick up your bow.”

I watched Judah and saw that it was difficult for him to keep the shoulder low. He did his best but it kept rising. Watching him, I felt a sympathetic pain. I rubbed my neck, silently hoping that he would master this so we’d both feel better.

It wasn’t all technique. Rick soon turned his attention to the other young players in the room as if noticing for the first time that they were there. But the focus was still on Judah. “What did you think of Judah’s playing?” he asked.

“It was bouncy,” one girl said.

“Good shifting,” said another.

“Judah was having a good time,” a boy said.

Now, with the new round of correction, critique, and encouragement, the child would play the piece again. After fifteen minutes, Rick would gently move on to the next young cellist. And the process of music, correction, encouragement, and group critique would begin again.

Rick’s questions to the group would vary as the week went on. “What food did Sarah’s piece sound like?” he’d ask. “Like chocolate,” said one child. “Like juicy red meat,” said another.

“What color?” “Red.” “Purple.” “Green.” “Snow!”

Time whisked by. Judah played cello a good five hours a day for five days straight and didn’t complain, even when I reminded him during a break that we’d have to spend a few minutes practicing. In the evening, the children put down their instruments and the faculty made music. One night a teacher played a gypsy-like piece by Ravel that began on stage but soon had her dancing through the audience of children.

“What did that make you feel like?” she asked the children when she was done. By this time they were more than musicians; they were experienced critics who could express their feelings about the music. The answers were so sophisticated that they took my breath away.

“It made me feel like crying,” said one little boy.

“No. It was happy,” said another child.

“Well, kind of happy and sad, like flying. It’s exciting but scary.”

“I felt something different,” said another. “It was like . . . like rolling down a hill so fast, you can’t stop!”

MUSIC MOMS AND DADS

Suzuki camp introduced me to the musical equivalent of the Soccer Mom, that devoted and sometimes pushy parent who, the stereotype goes, spends most of her time in the family minivan ferrying her offspring to soccer games and arguing with the coach for preferential treatment for her kids. Instead of carrying extra sneakers, socks, shin guards, and jerseys, the Cello Mom will carry a small stool (little cellists need little chairs), rosin (a chemical mixture rubbed on the bow to increase friction), extra strings, and sheet music. Between sessions at Suzuki camp, legions of music moms and dads—and sometimes grandparents, aunts, and uncles—could be seen toting the musical paraphernalia. Every child had a chaperone.

Some parents were musicians but this was not about their own playing. If any parents brought instruments along to Suzuki camp they didn’t show them in public. The only taste of music-making we parents experienced was the “group singing chorus” where parents and children were encouraged to do voice exercises and sing together. Judah and I went once to the group singing chorus but found it totally boring. We were already musically bonded so we decided to cut that class.

Parents were expected to attend all classes with their children, except for orchestra. While the kids were in orchestra, we parents were encouraged to come to special classes about how to be a good Suzuki parent. There were sessions on such topics as “How to Encourage Good Practicing Habits,” “How to Create a Music-Friendly Home Environment,” and “What to Do When Johnny Wants to Quit.”

We gathered in a classroom on an upper floor of the Hartt School while our musical prodigies were in the studios below. It was a diverse crowd, although older parents, almost all of them women, tended to predominate. There weren’t too many young moms in their twenties with a brood of kids. This was more the domain of the privileged older parent with one or at most two children, kids whom they could dote on. And while this was a BlackBerry and cell-phone crowd, parents paid attention. They did not pull out their PDAs. They had invested in their child’s musical education and recognized that it wouldn’t happen without them.

What inspires such parental devotion?

I am not sure about other parents, but for me it was a combination of emotions: the pleasure of the music, of course, but also anger and sadness. Simply put, I wish someone had done this for me. When I was six and seven and eight why didn’t anyone nurture my musical gifts? I sang in school plays and in the synagogue, and I never tired of listening to music and watching musicians make music, either on television or live. Why didn’t someone put a violin or cello in my hands? Why didn’t my parents take me to music lessons? Why didn’t they present me with the challenges of musical notation and vibrato and the camaraderie of the orchestra?

Perhaps my parents were unable to give me these things because they were so consumed by their own hard times. They divorced but they had no game plan after that. Neither of them could handle three

young boys alone so we spent our childhoods shuttling between their homes and the homes of aunts and uncles and grandparents. Even if someone had put an instrument in my hands, I suspect it would have been for naught. All of the elements that Shinichi Suzuki insisted on were absent: consistency, practice, discipline, support, and environment.

As an adult, I was trying to give my child everything I missed. Perhaps the cello was just a symbol. Was all this healthy? Was I simply displacing my own needs? Was I projecting onto Judah my own unfinished business with my parents? Was I trying to live through my child? Was I trying to make my dreams his dreams? Was I being entirely selfish?

Not entirely, I thought, because there was one other element in play here: guilt. In some ways I had let my older children down by not always being there for them musically. Shira and I made sure they had exposure to music and instruments but I never became their Music Dad.

The reasons for that were understandable. The years when Adam and Emma were six, I was a daily newspaper reporter, a job that often took me away from home and away from the family. At those times I was working at the Times Square newsroom and I worked what I like to call 24/6. (I am a Sabbath observer so I usually managed to take off on the seventh day.) I was building a journalism career, and that meant regularly missing family dinners and, when I was at dinner, taking calls then and at all hours. Taking calls in the 1980s meant something quite different than it does today when cell phones and laptops are ubiquitous.

On a good day in the eighties, I would meet my deadline, leave the office at six, get on a train to our house in suburban New Rochelle, and be home by seven. From six to seven I was what we called “out of pocket,” meaning that if my editors had any questions, they couldn’t reach me until I walked into the house. Shira’s first words when I walked through the door were often “call the office.” Sometimes I would manage to begin dinner with the family (who had waited my arrival) and then the phone would ring. And if the editor had a question, he just couldn’t shoot over the copy onto my laptop. He’d have to read the changes to me word for word. Meanwhile, I would be signaling to Shira and the kids to go ahead without me.

Still, I loved my work. I almost never turned down an assignment. I wrote about murders and robberies and train crashes and other catastrophes. I covered politicians and celebrities and wrote obituaries and book reviews. And I traveled around the country and around the world, including a monthlong stint in southern Africa. And I started my first book during a two-week vacation (during which Shira took the kids to Boston) and finished it on a series of Sundays (when, again, Shira was with the kids). During those years I left the bulk of parenting to Shira. She threw herself into the task with passion, creativity, and joy. Although we lived in the suburbs, Shira did a whole lot more than open the back door and tell the kids to play in the yard. She took them to the storytelling hour at the local public library and then led them through the stacks to pick out books for reading at home. She took them to state parks and fine art museums and gave them each a sketch pad to draw what they saw. She entered contests on radio stations and won free tickets to amusement parks and the circus. And Shira was the Music Mom during those years, taking Adam and Emma for lessons with a wonderful woman named Rosalyn Tobey, who gave them piano lessons in her home studio surrounded by the paintings of her husband, the muralist and painter Alton Tobey.

I was not part of these adventures and often felt left out. I couldn’t wait to get back at night to hear about them. I remember coming home to find Shira reading The Velveteen Rabbit or Charlotte’s Web or Where the Wild Things Are to Adam and Emma. All three were curled up on the couch, the kids in footsie pajamas, their hair still wet from the bath. They’d look up at me as if to say, “Who’s that? Why’s he breaking the magic spell?”

By the time Judah was born in 1995, however, my life had changed radically. We had given up our suburban home and moved to Manhattan. Instead of a life of parenting and freelance writing, Shira took a full-time job, first as a publicist and writer, and then as the head of her own public relations and marketing firm. As her professional life became busier and more demanding, mine became more manageable. I quit the newspaper business and, by the time Judah was turning six, I was a tenured professor at Columbia. I had responsibilities, of course: classes to teach, papers to evaluate, faculty meetings to attend, and my own research pursuits. But as a professor I also had summers off. And long holiday weekends. And five weeks off between the fall and spring semester. I had what inspirational speakers might call “the gift of time.” I decided to make Judah’s music education my project.

I HAD BIG DREAMS for Judah. After his lessons with Laura, I would walk her to the front door of our apartment, hand her a check, and set a time for the next lesson. I was so thrilled with the progress she was making with Judah that I was giving her spontaneous raises. She started at sixty dollars an hour, but after a few months I told her she was underselling herself and I gave her seventy. Then I started giving her eighty.

One day, while seeing her out, I had to ask. “So Laura, how good is Judah?”

“He’s good. He’s real good,” she told me. “And he loves it so.”

“I marvel at the way you encourage him. The support. The cheers. The standing ovations.”

“That’s all part of my method,” she said with a smile.

“Of course, but, Laura, do you think Judah could be a professional cellist? I mean, do you think he could get into a conservatory? Maybe make a career out of this?”

Laura looked at me oddly. She was kind of sizing me up like she did the first time we met on Broadway. “Ari,” she said patiently and kindly as if she had had this conversation with eager Music Dads before, “he’s a boy; a talented boy, but still a boy. Give it time. Now, make sure he practices tonight.”

THE INTERSCHOOL ORCHESTRAS OF NEW YORK

Judah’s musical life was divided between the school year, when he took lessons with Laura, and the summer, when he’d go to music camp. He attended a Jewish primary school in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, where his day was already chock-full of subjects. He took all of his regular classes—math, science, social studies, English, gym, and art—plus a heavy complement of religious studies, including Bible, Talmud, and Hebrew. Jewish Day Schools do a lot of things well, but music isn’t one of them. While there was some music instruction and a lot of singing, the school did not offer orchestra opportunities like many public and private schools. There was no room full of instruments that kids could try out. The few kids who had serious music instruction were learning with private teachers.

This made Judah and his cello rather exotic in the school. Even in third and fourth grades, Judah was known in school as “the cellist.” And, frankly, he loved to flaunt it. He’d carry it to school assemblies with pride.

Still, being the only cellist at his school wasn’t ideal for Judah’s musical education. He needed to play with others. When he was in sixth grade, the mother of a young violinist in his school told us about an organization called the InterSchool Orchestras, which ran seven performing musical groups in New York City. Judah auditioned for ISO’s youngest group, known as the Morningside Orchestra, and was given a seat in the cello section. Unlike me, auditions, rehearsals, or playing in public did not faze him. He was a natural.

Rehearsals for the Morningside Orchestra were held every Tuesday at four o’clock, which made sense for children in public and private schools, but not for Judah, whose school day ended at a quarter past four. After pleading for some early release time, I got Judah excused from his last period at school and took it upon myself to pick him up each Tuesday at three thirty.

I had my routine. On Tuesday mornings I’d bring Judah’s cello to work with me and, at the end of the day, drive with it to pick him up at his school. His eyes would light up when I arrived to get him, although I couldn’t be sure if he was excited about playing in the Morningside Orchestra or getting out of school early. Then we’d race downtown in time for him to unpack

his cello and be ready for rehearsal.

The Morningside Orchestra was a wonder to behold. Little kids—ranging from seven to thirteen—were arranged in a semicircle facing their conductor, a cheerful, pudgy, and often ebullient man named Robert Johnston. This group of children had all the hallmarks of Upper West Side of Manhattan privilege: braces, pigtails, designer knapsacks, cell phones, school uniforms, and a gaggle of nannies and parents who waited patiently during the rehearsals. Each child held an instrument, often in the half or three-quarter size. There were violins, cellos, flutes, clarinets, and one oboe. The conductor kept them engaged and amused with corny and self-deprecating humor.

“Measure seventy-one,” he’d call out, signaling the point in the score where he wanted the orchestra to begin. “Measure seventy-one! My age!” In fact, Robert was barely forty, but the line always got a laugh.

“You’re sounding lethargic,” he said one night, and then went about defining the word by sticking out his stomach and lolling around the front of the room like a stuffed monster who, he explained, just ate a huge Thanksgiving meal. “Okay,” he’d say when the laughter died down. “Measure 161. I said Measure 161! My IQ.”

One day Robert handed out the score for a new piece of music, a lyrical composition by Carl Strommen called “Irish Song,” and asked the group to sight-read the music as he conducted. The piece was beyond their abilities and the young musicians quickly got lost. Robert stopped. “What’s the most important thing about sight-reading?” he asked, hands on his hips.

The youthful orchestra members called out answers.

“Rhythm?” one little girl asked tentatively.

“No!” he shouted.

“Sound?” another ventured.

“No!”

“Intonation?”

“No!”

“Melody?”

“No! No! No!” he said, pounding his music stand. “The most important thing about sight reading is courage. You have to have courage!

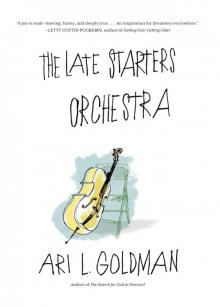

The Late Starters Orchestra

The Late Starters Orchestra