- Home

- Ari L. Goldman

The Late Starters Orchestra Page 4

The Late Starters Orchestra Read online

Page 4

With her children out of the house and the shop closed, Eve’s thoughts returned to music. “One day I was walking by the Third Street Music School and saw this sign that read: NEW CELLO CLASS FOR ADULT BEGINNERS. LIMITED TO THREE STUDENTS.

“To be honest, I was always terrified of the cello,” she told me, explaining that she found “daunting” the notion of carrying it around and tuning its four strings. “But I figured I should confront my fears. . . . So I walked in and signed up. They even supplied me with a cello.” It was not a natural fit. The cello was big for her small frame, but Eve compensated by moving around the instrument more like a double bass player in a jazz quintet than a cellist in an orchestra.

She picked it up at sixty-seven and still hadn’t let go a decade later. From what I could see, in those ten years she had achieved something extraordinary. In ensembles, you don’t often hear your fellow musicians playing individually. It’s one of the aspects that I like about it. You can hide and even get lost in the crowd. You are in an orchestra but you’ve got cover. Every so often, though, a cello solo is called for and, for that, the first cellist takes center stage. One day at rehearsal, we were playing a short, upbeat, dance-like piece by the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg called “From Holberg’s Time,” a composition written in the nineteenth century meant to evoke the eighteenth. As often happens, the violins carry the melody at first and then it shifts to the cellos or more precisely one cello. The cello ensemble is instructed in the music to “pizz,” which means to pluck strings in what is properly called pizzicato. My fellow section cellists and I were plinking, while one cello—Eve’s—began to intone the melody. It took my breath away.

I dared not play with her, but I sang along with her melody, quietly and under my breath.

If rhythm emerges from the body, melody springs from the voice, Mr. J would say. Everything is a melody, even a baby’s cry. It may start with a whimper and escalate to a screech. But then the baby finds the mother’s breast and a gentle cooing is heard. Of course, the baby doesn’t know he’s singing, but he is. He doesn’t know he is in the middle of a drama—a grand opera, perhaps—but he is. Think of melody as a plot, a tale of love or conflict or struggle. Melody tells a story.

When I heard Eve play, I heard the melody but I also heard her story, the story of a late starter who, to my ears, played like an early starter. How did she become that good? After the rehearsal, I asked Eve about the place of music in her life. “What does your typical week look like?” I asked her. Maybe if I followed her model, I could play like that, too.

I was astonished to learn that music wasn’t a side dish for Eve, but the actual main course of her life. Indeed, she was actively engaged in playing every single day. Her week was all music, all the time:

Sunday: The Late Starters Orchestra

Monday: Amateur Chamber Music at the 92nd Street Y

Tuesday: The Downtown Symphony

Wednesday: Cello lessons with Allen Sher, formerly of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

Thursday: Trombone lessons at the Third Street Music School Settlement

Friday: More coached chamber music at the 92nd Street Y, these sessions specifically for those sixty or over

Saturday: Practice, practice, practice.

It all made sense, except Thursday.

“Trombone lessons?” I asked.

“I couldn’t resist,” Eve said with a smile.

THE NEXT CHAPTER

What Eve was experiencing in her late seventies—and what I was beginning to feel in my late fifties—is part of a much larger trend. Simply put, people are living longer, and, with leisure time increasing and jobs disappearing, often have more time on their hands. Over the course of the twentieth century, life expectancy in America rose from an average of just over forty-nine years to seventy-seven and a half years. The baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964—my generation), the twentieth century’s noisiest and most demanding generation, are now moving into their sixties and their quest for learning, meaning, growth, and attention is unabated. American universities are increasingly catering to this population by opening up their classrooms and offering special nondegree programs to the boomer set. Sociologists have a variety of names for the transition into this phase of life.

Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, a Harvard sociologist, calls it “the third chapter” and writes about it in a book by that name. She tells the stories of people who, late in life, are learning to speak a foreign language, play jazz piano, surf, act, and write plays. What characterizes them all, she writes, is “the willingness to take risks, experience vulnerability and uncertainty, learn from experimentation and failure, seek guidance and counsel from younger generations, and develop new relationships of support and intimacy.”

Patricia Cohen, the author of In Our Prime: The Invention of Middle Age, believes that education is the key. Discussing a brain study conducted by two psychologists at Brandeis University, Cohen writes, “For those in midlife and beyond, a college diploma subtracted a decade from one’s brain age.”

Music is even better. I can hear Mr. J saying. It shaves twenty years off brain age. Rhythm springs from the body and melody from the voice. But harmony, he taught me, springs from the mind. To find harmony we must find balance. It is about constantly making judgments. Above all, harmony is exercise for the mind.

Several studies show that musicians tend to remain sharper in old age than those who do not have music in their lives. Those with musical training outperformed nonmusicians in both visual and verbal memory tasks. It wasn’t only in aural memory that they exceeded the others; it was also in remembering what they read and saw as well. Those who started musical training young had a greater advantage, but even late starters did better than nonmusicians in memory tasks.

In one study, conducted at the University of Kansas, researchers compared three groups of seventy healthy older adults ranging in age from sixty to eighty-three. They divided their subjects into three groups: nonmusicians, low-activity musicians (one to nine years of musical training), and high-activity musicians (ten years or more). The researchers did their best to control for every possible condition of importance, including intelligence, physical activity, and education. Still, the results showed that the more music, the better the memory, the quicker the processing speed, and the more adroit the cognitive flexibility. Music, it seemed, was able to take an eighty-year-old mind and turn it into a mind more befitting of a sixty-year-old.

You can read about the benefits of adult learning in such places as Psychology Today, a magazine where the median age of readers is forty-five. (One recent Psychology Today feature article had this headline: MUSIC LESSONS: THEY’RE NOT JUST FOR KIDS ANYMORE.) And, of course, music isn’t the only way to sharpen the mind. There are also numerous inspirational books on the market touting the value of any kind of lifelong learning, books with the titles Aging Well, The Art of Aging, From Age-ing to Sage-ing, and this one with a cautionary title, The Denial of Aging: Perpetual Youth, Eternal Life, and Other Dangerous Fantasies. Magazines like AARP often feature stories about actors, writers, and painters who come to their craft late in life. Julia Child did not even know how to cook until her late thirties; Grandma Moses didn’t pick up a paintbrush until she was in her seventies; Tillie Olsen published her first book at forty-nine; Danny Aiello didn’t act until he was forty. However, in all these compilations, there is no list of great classical musicians who start late.

Guitarists, yes, but cellists, no.

In his book Guitar Zero, Gary Marcus writes about his personal quest to learn guitar as he approaches his fortieth birthday. Marcus, a psychologist, takes comfort in the stories of rock stars who came relatively late to their craft, like Patti Smith, who didn’t seriously consider singing until her midtwenties; and Tom Morello, who didn’t pick up a guitar until his late teens.

At thirty-eight, Marcus knew that the cards were stacked against him but he believed that he could master the guitar. “I wanted to know whethe

r I could overcome my intrinsic limits, my age, my lack of talent,” he writes. In the course of the book, he actually becomes quite competent on the guitar.

Marcus also revels in the ignorance of many famous guitarists when it comes to reading music. “None of the Beatles could read or write music,” Marcus notes, “and neither can Eric Clapton.”

It’s a good thing none of them played a classical string instrument. Cello is different. An ability to read music is required and there is no greatness unless you start young. Very young. “A string player should begin at 5,” the great violinist Alexander Schneider said. “Later is too late.”

ORIGINS

When I was five, string instruments were the farthest thing from my life. On the eve of my sixth birthday, my mother left my father in Hartford, Connecticut, and I began a new life with her and my two brothers in a small apartment in the Jackson Heights section of Queens, New York. Her leaving was the first salvo in a divorce proceeding that was to drag on for a good part of my childhood. For me, my parents’ separation and eventual divorce meant geographic dislocation, emotional and financial hardship, and family dissention that, quite remarkably, lasts to this day, even though my parents are long gone from this earth.

The one bright spot in my young life was music. I sang. I sang on the streets and I sang in school and I sang on the subway and I sang in bed and I sang in the synagogue. I had a remarkably good, clear, and energetic voice, one with distinct timbre, flexibility, and range.

It was very important to my father that I sing in the synagogue. Music, the music of the synagogue, was a link that kept us close even as I moved away and saw him only on weekends and holidays. My father wanted me to use my gift for the glory of God. From the time I was very young, he trained me to sing the solos that a small child can lead, such as the concluding hymns of “Aleynu” and “Adon Olam.” And, most of all, he trained me for my bar mitzvah, the day that I would be able to lead the adult congregation in prayer.

On the weekends that I spent with my father in Hartford, we would rise early Saturday mornings to attend synagogue. As Orthodox Jews, we did not take the car, no matter how hot or cold the weather. We walked in winter snowstorms and in spring rain showers. In traditional Judaism, to ride in the comfort of your car is a violation of the Sabbath, but to walk in terrible weather is fine; a mitzvah, even. Outside of traditional Judaism, our walks might not make much sense, but I wouldn’t have traded that time with my dad for anything. As we made our way to synagogue, about a ten-minute-long stroll, we held hands and sang. My dad would have me practice the special songs for Shabbat and we would talk excitedly about how we could innovate with extra melodies and vocal flourishes. Our voices resounded through the early morning streets.

I was loud for a little kid and could even project in Orthodox synagogues, which, in keeping with traditional Jewish law, did not use a microphone on the Sabbath. My bar mitzvah, held at the Orthodox Young Israel of Jackson Heights in Queens, New York, in late 1962, was a festival of song—with me as the star. Most bar mitzvah boys—there were no bat mitzvah girls in Orthodox synagogues in those days—read the Torah portion (a selection from the Five Books of Moses) and the Haftorah (additional selections from the Prophets). My voice was so good and renowned in our little circle that I was allowed to take over the whole service. I led the morning prayers, Shacharit, and the so-called “additional service,” Musaf, incorporating melodies both traditional and new. I sang songs inspired by the young State of Israel and by Hasidic melodies, especially as interpreted by the singing rabbi of that era, Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach. I even incorporated some of the vocal techniques and inflections I had learned from my folk heroes. One friend told me I sounded like I was auditioning for the Kingston Trio.

Without a banjo, of course. There were no musical instruments on the Sabbath either. No banjos and certainly no cellos. The Bible is sparing in its references to instruments, most of which were played to honor festivals and kings and to accompany the sacred service in the ancient Temple. The Encyclopedia Judaica lists nineteen instruments referenced in the Bible, including the lyre, the lute, the recorder, the harp, and a variety of horns, drums, and bells. Psalm 150 includes a veritable orchestra. “Praise God in his sanctuary,” the psalm begins. “Praise him with the sound of the shofar, praise him with the harp and the lyre. Praise him with the timbrel and dance, praise him with stringed instruments and the pipe. Praise him upon sounding cymbals, praise him with loud crashing cymbals.”

The harp and the lyre were used in the ancient Temple on the Sabbath, but after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE and the dispersal of the Jews into exile, the rabbis forbade their use on the Sabbath and were even ambivalent about music during the rest of the week. The nation of Israel was in mourning, the rabbis declared, and celebrations should be toned down. Music was still played at weddings, but even Jewish weddings are famously muted, even to this day. That is why a glass is broken. Even at our happiest moments, part of us is still in mourning for the loss of the Temple.

And why not? Even the wedding scene in Fiddler on the Roof is broken up by the arrival of the Cossacks. It is a most happy day when, despite Tevye’s initial plan, his daughter Tzeitel marries Motel the Tailor. The scene begins with the sentimental “Sunrise, Sunset” and ends with the exuberant “Wedding Celebration and Bottle Dance.” And then, at the height of the celebration, the Cossacks arrive and upend Anatevka. Unrestrained joy is not part of Jewish culture.

The “classical” music of my youth meant one thing: the music of the synagogue. I didn’t know of Bach or Beethoven. I knew how to chant the Torah and Haftorah, ancient books that had their own musical notation and strict rules. Every word, for example, had an assigned note. Miss a note or, worse, miss a word, and the entire reading was flawed, so flawed in some cases the reading had to be done all over again. Folk music was my rebellion. It provided a relief from all that rigor and precision and allowed for easy harmonies and quick innovation. The folk musicians I loved—Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Tom Paxton, Joan Baez, Judy Collins, Joni Mitchell, early Bob Dylan and, above all, Phil Ochs—wrote and sang right from the headlines. Their music was fresh and inventive (even if it occasionally all sounded the same) and broke all the rules. It shaped not only my musical tastes but my social consciousness.

I attended an all-boys ultra-Orthodox high school in Brooklyn that did its best to wall us off from the corrupting influences of modern society, but the outside world inevitably seeped in. If I gave the Beatles little attention when they first came to America in 1964, it wasn’t because I was so immersed in the study of Talmud. It was because the British imports seemed downright frivolous singing “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “I Saw Her Standing There” when there was a war going on in Vietnam and race riots in the South. I was captivated instead by the folksingers who were fighting for peace, racial equality, and the rights of workers. Soon after my bar mitzvah in 1962, I picked up a guitar, mindful of the words scrawled on Woody Guthrie’s guitar, “THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS.” I sang Ochs’s “I Ain’t Marching Anymore,” Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and Guthrie’s “Union Maid.” My friend Marty, a fellow yeshiva rebel, and I would take our guitars to Washington Square Park and sing our hearts out, not for the coins people tossed in our beat-up guitar cases but to feel a part of the revolution happening all around us. Marty was by far the stronger guitarist, but I had the voice. He strummed and I sang.

And then something terrible happened. My voice changed. After my sixteenth birthday, I couldn’t reach the high notes—or the low notes—and the middle range was uninspired. At first, I tried to ignore it and continued to sing my heart out, but others noticed. I was passed over for honors in the synagogue. And Marty found another singing partner.

I put down the guitar and avoided the synagogue spotlight. The voice that had given me so much pleasure—and earned me so much attention and approval—was gone. I put all my energies in high school and college into my next favorite thing: writing. Whi

le at college at Yeshiva University, I discovered the student newspaper and found I loved newspapers almost as much as I loved music. I read the daily paper voraciously. I dreamed about it at night, even imagining that I was scanning the columns of the next day’s edition. Those were my rapid eye movements. I wanted nothing more in the world than to become a newspaper reporter. In college I wrote an article about the New York Times campus correspondent at Yeshiva, a senior named Harry Weiss. In the piece, I explained how the Times, eager to know what was going on on campuses around the country, had put together a network of campus correspondents, called “stringers,” and how Yeshiva became one of them. When Harry graduated, he made me the stringer at Yeshiva.

At nineteen, I had my toe in the door of the Times and I didn’t let the door close for the next two decades. I went from being a stringer to a copy boy—the lowest editorial job in the newsroom and one that hardly exists anymore because of technology—to news clerk to news assistant to reporter trainee to reporter. I had numerous beats, but I hardly ever wrote about music, nor was it much on my agenda, that is, until one day, quite by accident, I ran into an irresistible musician who taught cello.

I was, at the time, a newly minted reporter in the newspaper’s Long Island bureau and on my way to an interview in an old office building when I knocked on the wrong door. A short, stocky man with a beautiful shock of white hair came to the door rubbing sleep from his eyes. The room behind him was dark but the light from the hallway illuminated a most beautiful wooden cello case behind him.

Forgetting why I knocked in the first place, I asked, “Do you play the cello?”

“Yes,” he said in a thick German accent, “do you want to become one of my students?”

“Yes,” I responded without hesitation.

A week later I returned to his studio, a simple room with the wooden cello case, two cellos, a viola de gamba (an early music instrument sometimes called a “cousin” of the cello), an upright piano, a tea kettle, a full-length mirror, a table, two wooden chairs, and a mattress on the floor, which the cellist used for naps between student appointments. His name was Heinrich Joachim, but I came to call him Mr. J.

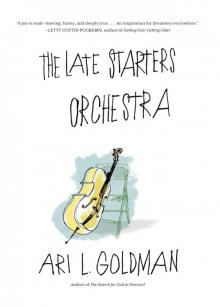

The Late Starters Orchestra

The Late Starters Orchestra