- Home

- Ari L. Goldman

The Late Starters Orchestra Page 17

The Late Starters Orchestra Read online

Page 17

Energetic was her middle name. When I had problems with my rhythm, she jumped around the room, almost as if she was on an invisible pogo stick, to demonstrate the proper rhythm.

On day three, though, her mood turned dark. “Brutal private lesson with Joanne,” I wrote in my diary. “The room is cold and damp. Joanne is wrapped in a coat and is congested. Her ugly little dog is sniffing about in the corner. Joanne has lost all patience with me. She hurled the most painful insult: ‘You are playing like you did before,’ she declared.

“I feel like I am disappointing yet another teacher,” I wrote. “I am not sure I can ever get better.” But Joanne was determined. As I was playing, she grabbed my right elbow and began directing my bow, back and forth, back and forth. First she guided me firmly, then roughly, pushing my arm like it was a child on swing.

She laughed, but I could feel her frustration, even her aggression.

“I guess you’ve worked with all kinds of students,” I said to break the tension.

She took her hand off my arm. “Little ones, big ones, professionals, semiprofessionals, superprofessionals, and everything in between.”

I had to wonder: Was I the worst student she ever had?

I came away from that session dispirited. That night I sat in the chilly summer night air on the steps of the Lubec Memorial Library, which had mercifully left its wireless connection on and sent an e-mail to Shira. “What am I doing here?” I wrote. “This was a dumb idea.”

THE WEEK AT SUMMERKEYS built to a crescendo with musical performances on the last night. This was finally the time we would be able to hear the other groups—the pianists and the mandolin players—perform. And they would hear us cellists. Our little cello ensemble had been preparing a variety of pieces for the performance, mainly transcriptions by Mendelssohn and Vivaldi, since there is really so little music written for five cellos.

Most of us were anxious. We planned to play four pieces together and then each take a solo turn. Ruth, who had been working all week with Joanne on the Saint-Saëns, was in good shape, but a student named Tobie was having a meltdown over her little slice of Vivaldi. “I’ve got major performance anxiety,” Tobie told me. But at least she had the courage to play in public. I felt so dispirited by my week at SummerKeys, I told everyone that I would not perform my Bach solo. I practiced it a hundred times but felt I was not ready for prime time, even if prime time meant a concert in the local church.

“I’m just not ready,” I told Joanne at our last lesson. I was bracing for an argument from her but she seemed relieved by my decision and didn’t press me further.

The concert was a success. I played with the ensemble and then sat out the solos. I was not sure anyone even noticed.

So here I was, ten weeks before my sixtieth birthday—with years of lessons behind me, a hundred nights of practice with Judah and on my own, and weeks spent at cello camps—and still no closer to my goal. If I couldn’t play in Lubec how could I play in Manhattan? I began to think that I would never get there.

The trip to Maine wasn’t a total waste. I did fall in love . . . with Ruth’s cello. I had rented it from her for a week and now couldn’t part with it. I figured that even if I ended up quitting in frustration, I knew that Judah would enjoy this instrument. It did have a beautiful tone. We had been renting a half-size cello for Judah in New York. Here was the full-size cello that he could step up to when he was ready.

I FLEW HOME FROM Maine, and Ruth’s cello came via UPS a few days later. Ruth sent it in a huge cardboard refrigerator box surrounded on all sides by foam rubber. It arrived in good shape—and still in tune. Although I was expecting that it would be a while before Judah was ready for this cello, he took to it immediately. It was the next step both in size and in sound. He brought out the best in the instrument. Soon after I returned to New York, we attended Judah’s middle school graduation, which included a musical presentation with Judah on cello.

On stage, waiting his turn, Judah appeared supremely at home. A group of his classmates was singing, and Judah was just jamming along naturally, like you or I would hum along. At times he spun his cello around on the end pin, just like a wild jazz musician might do. It made me nervous—I had just spent thirty-five hundred dollars on that instrument—but when Judah started to play I calmed down. I listened and realized that Judah on the cello was everything I was not: strong, precise, passionate, and consistent. I watched him not in jealousy but in awe. This is perfect, I told myself. Why do I need anything more? I have a son who is a cellist. And his music brings me great joy. Maybe this is the end of the story. This is the end of my cello dream. And it is fulfilled.

PART SIX

The Beauty of an Open String

R

What we play is life.

—LOUIS ARMSTRONG

I didn’t even want to touch my own cello, Bill, the battered one Mr. J sold me thirty-three years earlier. Late one night, I got out of bed, took Bill out of its case, and looked at it in disgust. “You’ve done nothing but frustrate me all these years,” I said angrily. “I hate you. I can never play you. I’m no cellist. I’m no musician. Who was I kidding?”

And, then, the cello answered me. Or maybe it was Mr. J.

Open strings.

What about open strings? I asked.

Play open strings.

Open strings, the simple act of running one’s bow across each string to get the four unadorned notes of the cello, A, D, G, C—each one a perfect fifth from the one before and after it—is arguably the easiest note progression one can play on a cello. Or the hardest. Sort of like breathing. You can inhale or exhale without a thought or you can be totally mindful of every breath.

Play open strings.

Play now? In the middle of the night? I’ll wake up the whole house. I’ll wake up the whole building.

Just play open strings. And, I promise you, for now, only you and I will hear it.

I grabbed Bill, sat down, and began to play. Open strings.

Now remember. On each string there is a spot, a sweet spot, where you draw the most sound. Find it. Find it and stay with it. Now close your eyes. And bow.

I played open strings. A, D, G, C. A, D, G, C. A, D, G, C.

Again. Again. Again. Again.

That’s beautiful. You have to think of open strings not as a series of notes, but as a song, as music. You are playing beautiful music.

I spent the better part of an hour finding the right spot, the sweet spot, and playing open strings.

Okay, Ari, enough for now. Go to sleep. But I want you to play open strings again tomorrow. And the next day. And the next. Nothing else.

And what do I play at my party? I asked. Open strings?

Maybe. But we don’t have to worry about that now.

I played open strings every day. But not only when I had the cello in my arms. I played open strings in my mind when I took the subway. I played open strings when I shopped for groceries. I played open strings when I walked the dogs. I played open strings when I taught my classes the next day. Open Strings, I was learning, was a state of mind, a continuous line of music that allowed for a serenity and calmness. Like water lapping at the shore. Like the paintbrush in the hands of an artist. Even if my hands were in my pockets, I could feel the bow moving across the string and hear its sonorous melody.

A few afternoons later, I was home playing open strings when I heard Mr. J again.

Now try the Bach.

I began to put my sheet music on my music stand.

No sheet music. Just play.

“The Bach” was Minuet no. 3, the piece that I failed to play at the concert at SummerKeys. I hadn’t even tried to play it since. It’s a simple melody and comes in two parts, one major and one minor. I played the first part from memory, and it never sounded better. I got lost in the minor part, but Mr. J didn’t seem concerned.

Ask Judah to help you. He’ll play along and you won’t get lost.

I hadn’t planned on asking Judah. T

he point was that I was going to play myself and prove to everyone, most of all myself, that I was a musician. But playing with him seemed right to me. Musicians play with musicians. Judah would lift my game.

Okay, I said, that’s one song. What else?

What else would you like to do?

I reached for the sheet music but Mr. J again stopped me.

What else can you do without music?

Come on, Mr. J, I can barely do something with music.

How about “Mimkomcha”?

It was the song that I sang at my bar mitzvah. The song that the composer Shlomo Carlebach was going to tell Bach about in heaven.

I bet I can do that, I said.

One more thing. You told Bill you hated him. That was good. Very good. In order to play cello, you must be able to say “I hate you” or “I love you” with complete honesty. Once you care that deeply, you can play “Mimkomcha” and anything else you desire. You’ve learned that music is more than notes and rhythms and strings. Music is emotion.

Now play, Ari. You don’t need Judah. And you don’t need me.

I told Mr. J that I loved him. And, suddenly, I felt that he had gone away, forever. And I was alone with my cello.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY

A friend of ours who works in publishing offered us a reception room high above Manhattan for my party. It was an open, airy, and flexible space and there were some decisions that had to be made.

I wanted classical music in the background, but Shira thought rock was a better choice to put the crowd at ease. I wanted the lights on bright so I could see people; she said dimming them would create a more festive mood. I wanted lox and bagels but she ordered Mediterranean. Though our styles often clash, I have learned to defer to her on all things partyish.

On that pleasant fall Tuesday night, September 22, nearly one hundred people gathered. The invitation promised cocktails, food, and a cello presentation called “From Bach to Carlebach.” As the room filled with family and friends, I drank in the sight of my party with a large measure of relief. I am not a relaxed host and yet it was impossible to ignore the fact that people were having fun. They were eating pita, olives, hummus, and falafel balls as Elton John, the Talking Heads, and the Rolling Stones—Shira’s selections—played in the background. There were people from every corner of my life—from my Uncle Norman, the chancellor of Yeshiva University, to some of the mischievous young children of friends from Rosmarins, our summer bungalow colony in the Catskills. Some of my former newspaper buddies were there, as were several university colleagues. A number of my former students showed up. Editors who’ve worked on my books came, as did friends from my synagogue and the Bruderhof, the Christian community in upstate New York that provided us with live-in nannies and impromptu music lessons when our children were young. Noah arrived with his cello and so did some of my pals from LSO. Our Hasidic Chabad-Lubavitch friends came, too, so the fashions ranged from black hats, long skirts, and kerchiefs to bare heads, shorts, and miniskirts.

I dressed in a tuxedo jacket and wore my favorite paisley bow tie. I topped off my ensemble with my black knit yarmulke. I don’t always wear a yarmulke. I don’t wear one at work or while teaching, but I do wear one at home, in synagogue, and at family and Jewish community events. It is a statement of who I am. And this was one of those occasions to declare who I am; I don’t think I took anyone by surprise.

Indeed I was barely conscious of what was on my head as I happily drifted through the party. People were eating, laughing, schmoozing, and drinking. It was wonderful to see the many parts of my life come together in one place. After a short while, Shira quieted the crowd and welcomed everyone. She made a sweet toast and then opened the floor for others to follow suit. A high point was when my daughter, Emma, took the mike. Emma proceeded to reminisce about how, when she was little, she had so many things rumbling around her mind that she often had trouble falling asleep.

“My dad would come into my room, sit on my bed, and sing me folk songs,” she recalled. “He sang ‘Leaving on a Jet Plane’ and ‘Kisses Sweeter Than Wine’ and ‘Long Black Veil.’ But my favorite was ‘Brown Eyes.’ At least that is what Dad told me it was called. It wasn’t until years later that I found out the song was called ‘I Still Miss Someone.’ And it was about a sweetheart with blue eyes, not brown. I have brown eyes so he changed the song for me.”

Turning to me with a shy smile, Emma sang:

Though I never got over those brown eyes

I see them everywhere

My dad he would rewrite folk songs

And kiss away all my tears

Emma’s voice was pure, sweet, and strong, reminding me of my long-ago lost boyhood voice. She took the song I first heard from Joan Baez and reinvented it. The years fell away. I saw myself sitting on the edge of my little girl’s bed, holding her hand, offering comfort in the best way I knew how—through song. Now a beautiful young woman, my daughter was singing to me, helping me on a journey to a new phase of life. I savored the magic of the moment, realizing that what I had given her had come back to me in ways well beyond my imagining.

Then it was my turn. Looking around the room, I realized that my web of relationships was built on familial bonds, friendship, music, work, and my religious life. People knew me as a teacher, colleague, friend, and fellow congregant. Almost no one there, though, knew me as a musician. The time had come to discover if I really was one. I was not nervous. I believed in my open strings.

“Over the last sixty years,” I began, “I’ve used words, millions of words, in books, articles, lectures, and countless conversations. But some things cannot be expressed in words alone. Words cannot express my thanks to all of you for coming tonight. Words cannot express my love for Shira, who has stood by me—and put up with me and my music—for all these years. Neither can words express what a blessing my children are. The mere thought of them fills me with joy, amazement, and pride. As my beloved cello teacher Mr. J used to say, ‘When words leave off, music begins.’ So tonight I want to express myself in music.

“Forty-seven years ago, at my bar mitzvah, I could sing ‘Mimkomcha’ by the great Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach. Like Emma, I hit all the high notes back then. I can no longer sing it—my voice isn’t what is used to be—but I can play it on the cello. I can, so I will. I also want to play Minuet no. 3 by J. S. Bach, but I cannot play it alone. So I have asked my son Judah to help me on cello and our friend Jay to join us on keyboard.

“And now, ladies and gentlemen, my birthday program, ‘From Bach to Carlebach.’ ”

Judah and I took our seats and tuned our cellos. I took a few extra moments to run through my open strings. Then we nodded to Jay at the keyboard and the Bach began. Minuet no. 3 is one of the most famous Bach pieces, and while I can’t easily create it here on the page, it’s a dance that you’ve heard a hundred times on the radio or in an old movie. It’s the quintessential minuet and goes like this:

More than a song, our performance was a musical conversation, first among Judah, Jay, and me, and then among all these friends in the room. I noticed more than a few people quietly humming along.

I played expertly through the “major” opening section but then I lost my way—as I feared I would—during the “minor” section. But Mr. J was prescient in suggesting that I enlist Judah’s help. While I sat out the minor part, Judah and Jay soldiered on without me. Luckily, the piece ends on a repetition of the major so I don’t think anyone noticed my momentary lapses. Not from the sound of the applause, anyway.

With the Bach properly dispatched, Judah and Jay left the stage and I was alone with my cello. I took a deep breath and played “Mimkomcha,” without sheet music and entirely from memory, with all of its over-the-top beauty, longing, and emotion. Again, Mr. J was right. This one I could do alone, without him and without Judah. Here’s a taste of “Mimkomcha”:

As I pulled the bow across the strings, I could feel the “soul” of the cello emerge and connect with my soul. For a moment

I was taken back to my bar mitzvah, singing with all my heart. My mother was there; my father was there; together, if only for a moment. Mr. J was there. Rabbi Carlebach was there, too, and I even think I saw Bach hovering about after listening to us playing his minuet. I found my rhythm. I found acceptance in the faces watching me. I found a sense of wholeness and joy in the moment as family, friends, music, and memory merged. It took sixty years to get there, even longer than the forty years the Israelites wandered through the desert. But the journey was worth it. I had reached my musical promised land.

FINALE

After the party, I felt that if I never played another note on the cello again, I would die a happy man. I was a musician. Maybe that wouldn’t be the first thing that the newspapers would write in my obituary (if there are still newspapers), but playing music is definitely and indisputably part of who I am.

I had reached my goal, but I couldn’t stop playing, of course. Since my birthday concert, many unexpected and wonderful opportunities have come my way. In my sixty-first year, as part of a citywide summer celebration, Make Music New York, I joined LSO for a concert in Central Park. Make Music New York takes place every year on June 21—the longest day of the year—and offers one thousand free musical events in public spaces throughout the city in what New York Magazine once called “exuberant overkill.” There are similar music-making events on June 21 in cities around the world.

LSO’s assigned spot was a sun-dappled pedestrian promenade overlooking Central Park’s storied Wollman Rink, the ice skating site best known as the setting for parts of the 1970 Hollywood tearjerker Love Story. It was a clear and crisp day. As it was the beginning of summer, there were no ice skaters going in circles to the sounds of Frank Sinatra’s rendition of “New York, New York.” Instead, the rink had been transformed into a very non–New York City scene: a carnival that you’d expect to see at a county fair. There was a Ferris wheel, a merry-go-round, and twirling rides designed to induce thrills and nausea. Country-and-western music blared from every speaker.

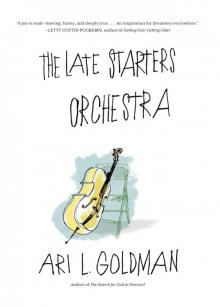

The Late Starters Orchestra

The Late Starters Orchestra